We’re In The Library

Exhibition Essay by Mona Filip

Sara Angelucci, Barbara Astman, Adam David Brown Michelle Gay, Ido Govrin, Vid Ingelevics, Jon Sasaki: We’re In The Library

Koffler Gallery, 2013

Libraries are sanctuaries from the world and command centers onto it: here in quiet rooms are the lives of Crazy Horse and Aung San Suu Kyi, the Hundred Years’ War and the Opium Wars and the Dirty War, the ideas of Simone Weil and Lao-tzu, information on building your sailboat or dissolving your marriage, fictional worlds and books to equip the reader to reenter the real world. . . . Every book is a door that opens onto another world, which might be the magic that all those children’s books were alluding to, and a library is a Milky Way of worlds.

– Rebecca Solnit, The Faraway Nearby

The new home of the Koffler Gallery is a former library – that of the now repurposed Shaw Street School. The move elicits reflection on the history that precedes us, finding inspiration for new beginnings in a rich past. For the inaugural exhibition, seven Toronto artists were invited to consider the former function of the gallery space and to respond with new works. In their respective practices, Sara Angelucci, Barbara Astman, Adam David Brown, Michelle Gay, Ido Govrin, Vid Ingelevics, and Jon Sasaki explore diverse media and ideas, but often gravitate around notions of memory and dissemination of cultural knowledge. Some of them have explicitly been preoccupied with the formal and conceptual aspects of books and text. For most, the project proposed a shift in perspective, sparking their keen scrutiny toward new territories that were nonetheless intimated in previous aspects of their artistic inquiry. Opening different directions linked to their core investigations, the artists created distinctive works that articulate a vibrant homage to the school library.

The prior lives of repurposed buildings continue to echo in their reincarnations. Exploring the notion that traces of the old school library still linger in the space, Sara Angelucci’s multi-part installation, The Readers, gives voice to students of generations past so that their readings may again reverberate within the gallery walls. A series of distinct elements orchestrate an emotional encounter: ten ghostly white plaster-cast book spines emerging from the wall, a layered audio recording of children reading, and a library cart displaying ten accordion books of anonymous portraits found in a gem tintype school album purchased on eBay.

Lamenting loss and memory’s ultimate ephemerality, Angelucci’s accordion books reveal the gradual disappearance of tintypes over time as they eventually fade to black, obliterating the faces of the already nameless children. All photographic media are inherently transient, despite their illusion of preserving an image. This impermanence – of photographs as much as buildings – emphasizes our own, though hope persists that our memories and stories might somehow endure. Angelucci’s soundtrack of recorded children’s book fragments attempts to restore a voice to the vanished children. Personal memory also informed the conception of The Readers. As a fourteen-year old, Angelucci was told one day by the school librarian that she looked like Anne Frank. Unfamiliar until then with Anne’s story, reading the diary was a pivotal moment in her development toward adulthood and understanding the world in a stark new light. Angelucci selected the books referenced in her installation by asking others to share similar stories that marked them deeply as children and remained connected to their identities.

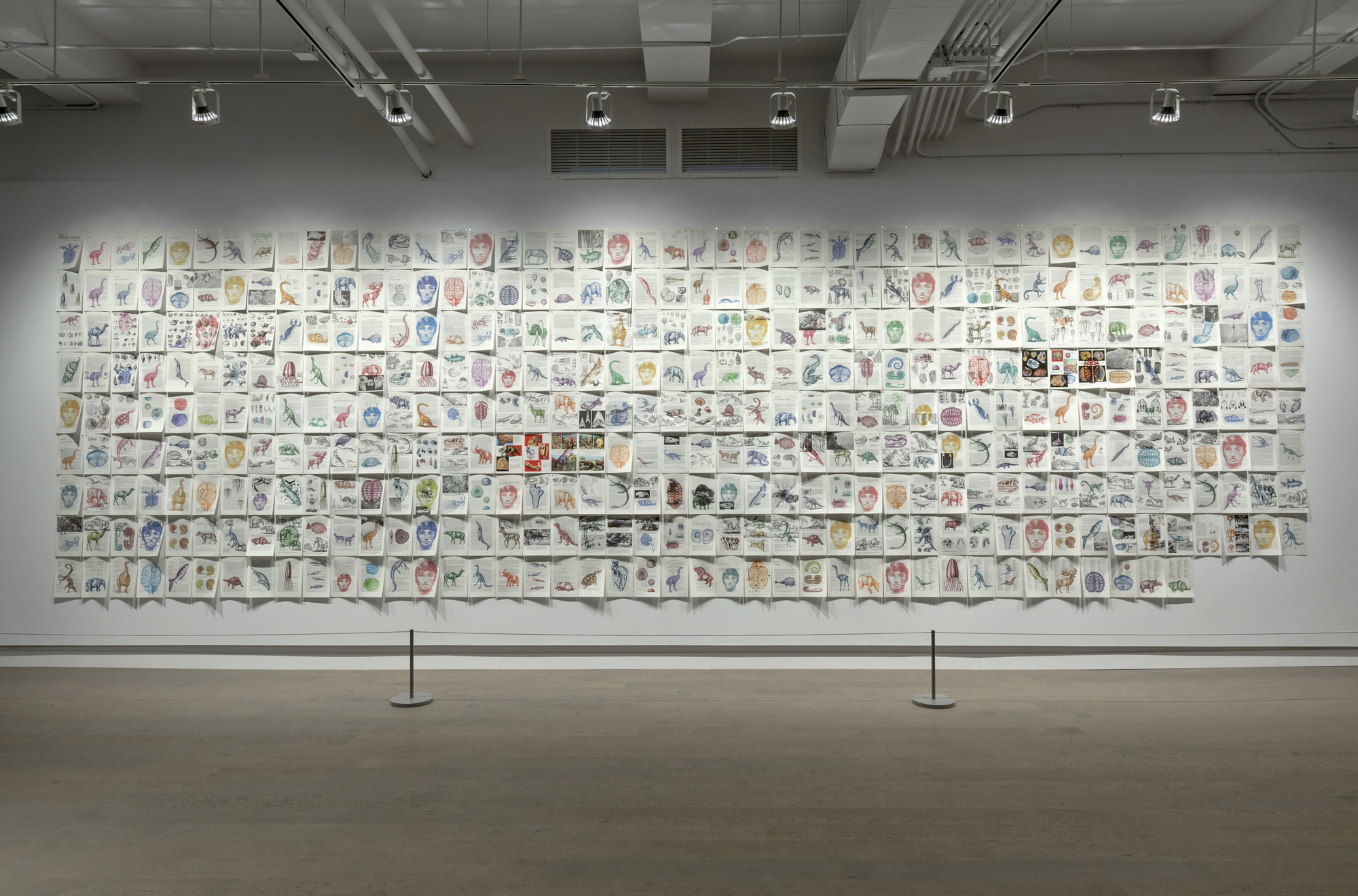

Great reading journeys and essential book discoveries often begin with a question asked of a librarian and an encounter with a volume filled with information and images almost incomprehensible but dazzling to the mind. A similar memory is at the core of Barbara Astman’s work in the exhibition, The Fossil Book. Wondering how we got here is one of the first inquiries we set upon. In Astman’s case, the librarian offered an answer to this quest by directing her to a children’s book on fossils.

Her universe expanded from the limited circle of her everyday experience, with a burst of new knowledge and fascinating creatures. Later, in university, Astman bought a scientific textbook on fossils as a reminder of the one she was lent as a child, which had nurtured her initial curiosity. Carefully taken apart and playfully invaded by digitally printed, enhanced colour reproductions of the beautiful original illustrations, the 401 pages of The Fossil Book celebrate the excitement and anticipation of the unknown worlds that open within the covers of a book.

Textbooks and reference tools are Adam David Brown’s subject of investigation as well. Subverting hierarchies of control and classification, he reimagines two emblematic cultural artefacts associated with notions of knowledge, language and colonialism. In New Order, Brown refurbishes a library-decommissioned set of the Encyclopaedia Britannica with custom designed canvas covers to form a de-saturated colour wheel. A 32-part grey scale thus replaces the alphanumeric index of the encyclopaedia. The newly formatted books have a fluid order that resists the notion of a beginning or an end. The grey scale is organized in a circle, so that no volume has primacy over another. Each shade of grey closely resembles the one next to it, making classification or hierarchy impossible. Placed as a sculptural object upon a slowly revolving base, the circular set offers no fixed access point. Introducing this new system overlaid upon the encyclopaedia, Brown reduces it to a collection of obscured information, shifting its function to an aesthetic form dependent on surface rather than content.

Furthermore, with Rosetta, Brown reinterprets a famous archaeological vestige – the Rosetta Stone – dating from approximately 196 BCE. The stele fragment contains a political proclamation from the period when Egypt was under Greek rule, translated into the three languages of the time and place: Egyptian hieroglyphic and Demotic, as well as the Ancient Greek of the ruling class. Both Egyptian forms of language were lost and unreadable by the 5th century. Napoleon’s army discovered the stone fragment during their campaign through Egypt in 1799 and the British appropriated it when the French surrendered to them in 1801. Residing in the British Museum ever since, the artefact became an object of national fascination in both countries, generating a competition to be the first to decipher it and a cult following to this day. Brown meticulously re-created the inscriptions of the Rosetta Stone texts in fine powdered chalk on blackboard. The instability of this representation plays against the seemingly eternal quality of the carved-in-stone original as a pronouncement on the fragility and transience of our own time and culture. Throughout history, civilizations fall prey to each other and are irrevocably transformed by the conquerors. Control of language ultimately determines who controls ideas.

Translation, transformation and cultural transmission are also central notions in Michelle Gay’s work, onwhatis. Collaborating with her brother Colin, Gay experiments with information technologies to poetically transform the ubiquitous desktop computer into a creative device. Through specifically developed software, the machine produces endless new versions of an ancient text by Parmenides, one of the first western philosophers to grapple with questions regarding the nature of reality. Only 160 lines of his text were ever recorded, however, citations, translations, dialogue and debates spurred by his concepts started during Parmenides’ lifetime, contributing significantly to pre-Socratic Greek philosophy. Many of these discussions were not written but shared orally. It was the philosopher Simplicius who quoted Parmenides in writing and his account became the documentation of reference. A great number of translations have been produced ever since and no singular version is considered as definitive, each attempting to clarify the previous and possibly shifting ideas along the way.

onwhatis continues this centuries-long chain of imperfect transmission and revision using three translations (Coxon, Burnett and Gallop) and submitting the text to further alterations, this time through a software producing new permutations in real time. Word replacements range from poetic to absurd, subtly changing meaning in a strange exercise that seemingly enables a machine to think about being and reality. Unpublished and ephemeral, the resulting versions evoke another mode of communication, reminiscent of the oral tradition.

Whispers, the sounds familiar to libraries everywhere, infiltrate the exhibition through Ido Govrin’s sculptural audio piece, Forty-Eight Adieux For Peace. Comprised of 192 small speakers set in a faux-fur and wood frame hung on a wall, the sound sculpture articulates a sensual and enticing survey of famous authors’ last books. A barely audible woman’s voice reads through a list of book titles by various authors. All titles are the respective author’s last book to be published during his or her lifetime. The mysterious sound lures visitors to an intimate closeness to the piece, the fur caressing their cheeks and tickling their ears. The sensorial experience subverts the otherwise highly conceptual content referenced by the recording.

Triggered by a serendipitous finding of two small brass plaques on site, affixed on the wall high above the former book stacks, Vid Ingelevics’ installation, There was a tornado, 1969, speculates on the nature of an undocumented, award-winning mural produced decades ago by students in grades 7 and 8 at the then-named Givins Senior Public School. The found plaques indicate that the students had won a first prize at the Canadian National Exhibition in 1969. Through research at the CNE Archives, Ingelevics determined that the students had produced a mural, winning

a Canada-wide competition, along with $50 and a trophy. The actual content of the mural is missing; only its subject, People of the World, is referenced in the records.

To “re-produce” the missing mural, Ingelevics asked the sixth graders currently enrolled at Givins-Shaw Junior Public School to research and draw their versions of what students in 1969 might have included in such a mural. The artist scanned and digitally deconstructed the resulting drawings and texts into smaller elements, some of which he then recombined to produce a ten-minute video. The final piece offers an overview of the content that the students of 2013 suggest their counterparts in 1969 – now roughly the age of their grandparents – might have drawn. Displayed along with the trophy, the brass plaques, and the CNE documents assembled into a museological vitrine, the video questions the ways in which today’s students learn about the past, often in a distilled form accessed only through contemporary online search vehicles.

Further testing the innocent world-view of school murals and their less ingenuous commercial counterparts, Jon Sasaki proposes an experiment that challenges the idealized, frozen moment of global harmony by restoring it to real life. His video work, After A Mural I Painted in Grade Four, takes its cue from utopian school murals everywhere and a 1971 Coca-Cola commercial. Featuring ethnically diverse young people gathering on an idyllic, sunny hillside, harmonizing “I’d Like to Teach the World to Sing,” the beautiful image in the Coca-Cola ad befits the commercial ambitions of a multinational corporation, but is stirring and heartwarming nonetheless. “Children holding hands around the world” is a hopeful and pervasive stereotype, but commercials last a mere sixty seconds and primary school murals depict a static, snapshot instant.

Sasaki proposes an experiment that aims to enact the utopian moment live, stretching it to an extended period of time and relinquishing any control over the participants’ reactions. To this purpose, he gathers a cast of children from diverse cultural backgrounds, asks them to form a circle to emulate the well-known images, and records them over the course of an hour as they attempt to hold the pose. Impatience, fatigue, boredom, and ultimately playful energy gradually take over the group, dictating the real dynamics and actions of the young participants. The circle of harmony rapidly disintegrates as spontaneous friendships are formed and individualities asserted. What begins as a contrived, “smile for the camera” exercise slowly develops into a chaotic but true “magic moment” where children break the rules and make up their own game.

Libraries are the place where all rules can be learned, but also where we realize how they can be undone and the name of the game completely changed. As portals to new worlds, school libraries are often where some of our first journeys of self-awareness begin. The artists in this exhibition engage the library as a place of exploration and social interaction, revisiting cultural icons, revelling in the mysteries of books, examining the communication of knowledge, and questioning idealized notions of education. Like expert librarians themselves, they open perspectives, answer our queries with new ones, and lead the way to more discoveries.

Epigraph: Rebecca Solnit, The Faraway Nearby (New York: Viking, 2013), 63.

1 Located at 180 Shaw Street, the building went through several transformations and name changes during its life span as an active school from 1856 to 2000. After being decommissioned, its remaining students were consolidated into the Givins-Shaw Junior Public School built in 1957 and currently still active at 94 Givins Street, next to the old Shaw Street building.

2 The selection of books in the installation comprised: Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl (ed. by Otto H. Frank and Mirjam Pressler), The Giver by Lois Lowry, Charlotte’s Web by E.B. White, The Story of Captain Cook by L. Du Garde Peach, James and the Giant Peach by Roald Dahl, The Little Mermaid by Hans Christian Andersen, Anne of Green Gables by Lucy Maud Montgomery, The Little Prince by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, The Jungle Book by Rudyard Kipling, and The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett.