Searching for the Erased Past and the Missing Future: Natalie Brettschneider in Toronto

Exhibition Essay by Mona Filip

Carol Sawyer: The Natalie Brettschneider Archive

Excerpt from catalogue Carol Sawyer: The Natalie Brettschneider Archive, produced by the Carleton University Art Gallery in collaboration with the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, the Vancouver Art Gallery, and the Koffler Gallery, 2020

“Art history has a history,”1 and it comes with baggage. As a field of academic study, it has been shaped by motivations and agendas—ideological, political and psychological. Since its foundational beginnings within European institutions at the turn of the twentieth century, the discipline has been framed by a vision of art as a progression of formal and conceptual advances. Steeped in patriarchal mindsets, this chronological approach to artistic activity places artists in relation to past explorations, inscribing them within an overarching narrative of stylistic evolution that elides specific social, political, geographic and cultural contexts. Attempting to articulate a monolithic account of art’s progress organized into neat categories and clear connections, this systematizing method omits voices and trajectories that contradict, complicate or elude assumptions of linear development and cohesive intent. Women, along with Black and Indigenous people, and all people of colour, regardless of gender, are relegated to the position of “other,” their work regarded only as a source of inspiration, challenge or contempt. Despite decades of significant feminist and non-Eurocentric interventions, this hegemonic thinking still reverberates in the way that many museums, collections and archives convey the story of art.

The present inevitably relies on the past to conceive possible futures. Whether intentionally or not, explicitly or not, what artists create from their geopolitically complex cultural positions responds to the historical past, while forging fresh paths for artistic endeavour. With new work, they expand, reject, contest or break away from previous ideas—in turn seeking, denying or confounding precedents. Of all artistic contributions, however, those unacknowledged and sidelined by the art history canon are more susceptible of falling into oblivion. Being unable to trace relatable predecessors and see themselves reflected motivates many contemporary artists to investigate the blind spots and erasures of official records to find evidences that enable more comprehensive reports of the past. In doing so, they carve space for their own stories to evolve.

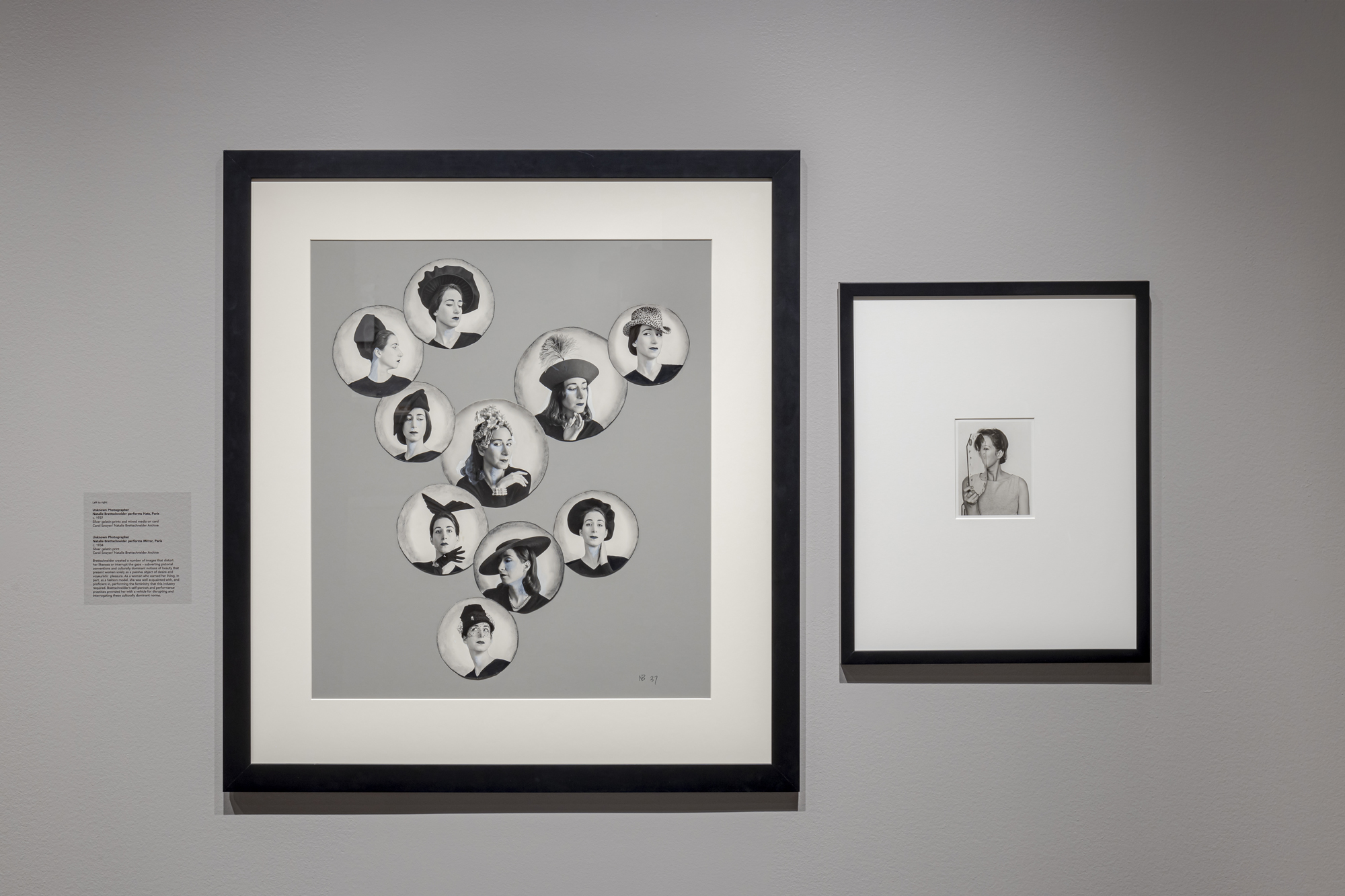

For Carol Sawyer, the act of pursuing a relatable predecessor became an artistic device at the core of her practice. To craft the Natalie Brettschneider Archive, Sawyer proceeds as an archivist, assembling a fiction as truthfully as possible to tell a needed story. She ends up telling many. Through convincingly manufactured photographs and documentary materials, the story of Natalie Brettschneider imagines the life and work of a genre-blurring, avant-garde artist who leaves a fragmentary trail through Modernism’s exclusionary narrative. Piecing together her biography, Sawyer (re)constructs a believable artistic forebear, while at the same time devising an excavation tool that brings to light buried or ignored accounts of real historical women’s creative achievements.

Unfixed and ever-growing, the Natalie Brettschneider Archive is a feminist intervention that splits open the would-be set-in-stone art historical record, drawing out a multitude of narrative threads and perspectives. Tackling a different angle with each iteration within different institutional and local contexts, Sawyer’s project keeps shifting focus to enrich our perceptions of the past, differencing the canon2 and so unlocking a spectrum of divergent futures.

As I write this, the project’s incarnation at the Koffler Gallery is still in development. As a non-collecting, contemporary-focused institution located in Toronto, the Koffler offers a distinctive set of circumstances and an opportunity to anchor the project in the richly diverse, overlying histories of the city at large. Two key intentions have emerged from initial conversations with Sawyer: to tell an increasingly fuller story and to critically consider who is telling it, sharpening the scrutiny of her creation, the artist Natalie Brettschneider, with both her drawbacks and potential. Placing her protagonist in Toronto at various dates between the mid 1940s and the late 1970s, Sawyer made research trips to Toronto and has been investigating the multicultural local context, looking beyond Brettschneider’s struggles, pressures and privileges as a white woman of that period to foreground some of the real histories of queer and racialized women who practised in artistic fields and contributed to the cultural milieu as her contemporaries.

At the Koffler Gallery the examination of Natalie Brettschneider as an imperfect character who sometimes subverts, sometimes reinforces, prejudiced historical tropes is heightened through archival presentation strategies. Even when focused on a single person, an archive is not an autobiography; it has a separate voice from that of its subject. This voice is Sawyer’s secondary output, another distinct persona who, as the curator/historian of the Brettschneider Archive, may enable a contemporary critical perspective.

“Power is at the centre of archival work: it is the power to retain, the power to discard, the power to partially shape what is remembered and how.”3 This awareness is equally relevant in the case of a fictional archive aiming to redress injustices. A heightened self-reflective ethic is required of its creator. By placing her invented predecessor at the heart of a historical period fraught with contradictions—on the one hand, progressive social movements and radical thought and, on the other, the enshrinement of patriarchal, racist, Eurocentric worldviews— Sawyer creates the opportunity to critically consider the possibilities and confines of those crucial decades for art practitioners who did not conform to prevailing outlooks, and the lingering influence of these exploitative ideas today.

Brettschneider’s imagined presence in twentieth-century Toronto occasions several encounters that shed light on women’s participation in the cultural scene of the time. As an experimental composer and singer trained in the bel canto tradition, Brettschneider followed the careers of Nisei opera singers Aiko Saita (1909–1954) and Lily Washimoto (b. 1909), who flourished in the 1930s and 1940s. Her attendance at several of their performances in Vancouver and Toronto is documented in scrapbooks with newspaper clippings. Her interest in fashion and fabulous headwear—dismissed at the time as lesser creative pursuits appropriate for women—led Brettschneider to cross paths with Minnie Soltz (d. 1989), the owner of Minette Millinery, centrally located on Yonge Street, and with Peggy Anne Jaffey (c. 1908–1995), who started Peggy Anne Hats in the mid-1930s. Documentary material indicates she might have been a client and even an occasional model for these prominent Jewish milliners.

Another enclave of Brettschneider’s Toronto connections places her within a circle of queer restaurateurs, Black jazz singers and Jewish cultural figures associated with the Park Plaza Hotel. Mary Millichamp (d. 1962) and Pansy Reamsbottom (1893–1972) ran the St. George Tea Room and the rooftop restaurant at the Park Plaza Hotel, then acquired property at 115 Yorkville, a dilapidated house, and turned it into a restaurant in 1948. Both the Park Plaza and the Yorkville restaurants became hangouts for dancers in the National Ballet of Canada, and Mary reportedly gave discounts to customers who worked in radio and television. Sylvia Schwartz (1914–1998), a portrait photographer whose father was a partner in the Park Plaza, documented the local scene, photographing prominent Black Canadian singers Portia White (1911–1968) and Phyllis Marshall (1921–1996), along with American stars like Duke Ellington.

These are currently but a few of Sawyer’s research leads in Toronto. Further strands will undoubtedly expand the breadth of stories that continue to enrich the Natalie Brettschneider Archive. A work in progress by its very nature, the Archive fittingly remains open-ended, as Sawyer strives to deepen her own critical awareness of intrinsic power dynamics and offer new insights into our cultural pasts. As Griselda Pollock writes:

In the end all our histories will be just that: stories we tell ourselves, narratives of retrospective self-affirmation, fictions of and for resistance that are, nonetheless, answerable to a sense of the real processes of lived and suffered histories. Thus to enter critically into the problematic of narrative, representation, history and the politics of meaning, we shall need self-awareness of who we are when we “tell a story,” what its effects will be, what is excluded and how contingent it will be, however diligent we are in our scholarship and research.4

The Natalie Brettschneider Archive is a compelling storytelling instrument. Motivations and agendas are impossible to avoid; the critical act is to recognize the limitations of subjectivity in the present. Through contemporary interventions that shake the foundations of dogmatic narratives, artists like Carol Sawyer can expose an ever more nuanced array of art histories and disrupt mythologizing views of art and artists. These acts of subversion and reform enable a fuller engagement with our living culture, nurturing hope for an unfettered future.

The title of this essay refers to Griselda Pollock’s question “If artists who were women were still being kept from public knowledge, what would happen if the institutions and their selective stories were not challenged in the name of both the erased past and the missing future?” See Griselda Pollock, “The Missing Future: MoMA and Modern Women,” in Modern Women: Women Artists at the Museum of Modern Art, edited by Cornelia Butler and Alexandra Schwartz (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2010), 28–55.

1 Griselda Pollock, Vision and Difference (New York: Routledge Classics, 2003), Introduction to the Routledge Classics edition, xxiv.

2 This phrase references Griselda Pollock, Differencing the Canon: Feminist Desire and the Writing of Art’s Histories (New York: Routledge, 1999).

3 Nina Finigan, “Are Museums and Archives Irredeemable Colonial Projects?,” Museum-iD magazine, no. 24 (2019), https://museum-id.com/are-museums-and-archives-irredeemable-colonial-projects/.

4 Pollock, Vision and Difference, xviii.