Mona Vatamanu & Florin Tudor: LIVING UNITS

Exhibition Essay by Mona Filip

Living UnitsMercer Union, 2008

I used to live in F6, 4th floor, apartment 32. I remember the fresh scent of the potted lemon tree blending with the smell of cold cement in the stairwell. Faded calendar pages decorated the hallways. Someone had claimed the last floor’s landing as their personal secret garden and blocked the access with a delicate wrought iron gate. The smell of fried onions or potatoes drifted through open kitchen windows. On the first floor, there was the woman who only went out to work on a small garden patch in front of her apartment. She shouted at us if we tried to play there, even though her daughter was among us. She painted the windows of her balcony in a green and orange pattern. Across, lived the old couple with a dozen cats. They always locked the back door of the building so non-residents couldn’t cut through and had to go around the block to get to the bus station. The hole in the bottom window of the front door made it easy though for my cat to sneak out as she pleased. It remained that way as long as I lived there. That was not the case with the ten-storey apartment building right across from ours, close enough to wave to the neighbors at night when the apartments were lit, or to check out the pickles stored on their balconies. There was once a small park, with perfect trees for climbing. But every bit of space had to be exploited. Or rather every trace of personal space had to be purged. More and more workers were being brought to the city to work in useless factories—the “Work-in-Vain Cooperatives” as we called them. Peasants were being forced to move too, the capital’s borders forcefully expanding to engulf their small houses, chicken coops and vegetable gardens. “New heights of civilization and progress” awaited everyone packed like sardines in standardized apartment buildings.

“Living under an ideological imperative is equivalent to living continuously with all the lights on—without a single moment of solitude, without a doubt, without mystery. You are the disarmed subject of an invasion. Little by little, you end up believing that your chances to evade and recover normality are none and that, in fact, normality itself is nothing else than an ideological construction.”¹

Aiming to implement the communist ideals, totalitarian states imposed a regimented way of life focused primarily on the suppression of individual freedom. Urban planning played an instrumental role in the systematic and ruthless invasion of private life. The city of Bucharest, as many others in Romania and Eastern Europe, suffered traumatic transformations under the communist system. Large-scale demolition led to the eradication of historical neighborhoods and the massive displacement of population, to make room for delusional symbols of grandeur and contrived urban prosperity. Enforced systematization replaced single family housing with conceptually, aesthetically and structurally deficient apartment buildings, as a demagogical attempt to provide affordable lodging while artificially increasing urban density. After the fall of the political system that produced them, the material residues of this utopia still stand. People continue to live with them, inhabiting forms which time proved inadequate for real human needs and desires. Negotiating these spaces involves a difficult process of remembering and forgetting painful public and personal histories.

The exhibition Living Units comprises a multi-media installation and photographic works by Romanian artists Mona Vatamanu and Florin Tudor. In their practice, Tudor and Vatamanu explore the visual, emotional and political aspects of architecture, its relationship to socio-political memory and subjective experience. Having grown up in a communist system, the architectural landscape represents for them a dramatic stage revealing layers of history and meaning. Urban sites are documents that speak of the clashes between the personal and the political ideology of a control state.

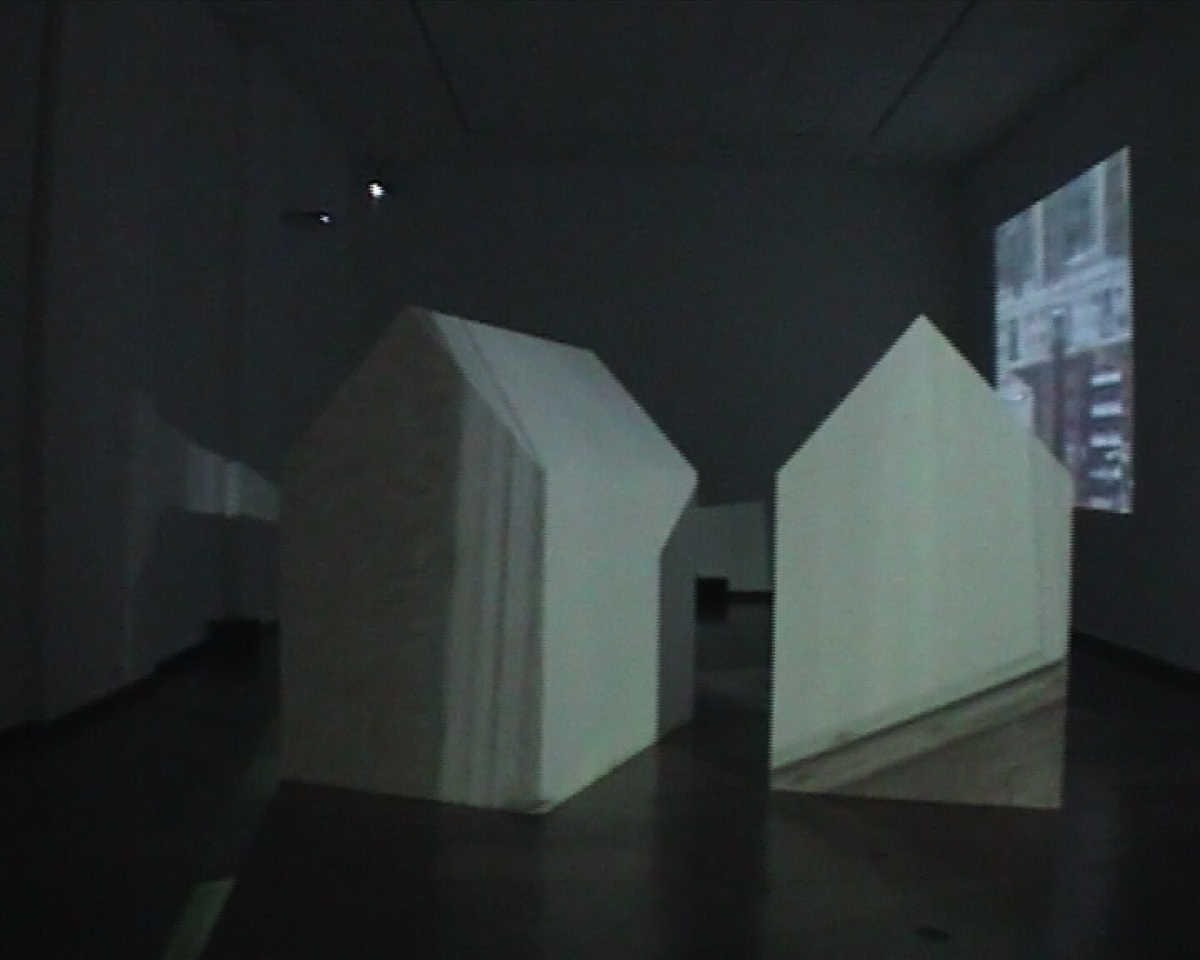

In Living Units, Vatamanu and Tudor create an immersive environment that emulates the oppressive monotony of socialist habitats, integrating the viewer as part of the landscape. Images of apartment building facades are projected onto two structures representing stylized houses, creating an ambivalent feeling of struggle. At first, the projections seem to impose their crushing presence upon the sculptural structures, overwhelming them, suppressing their individuality. A moment later, the images seem swallowed up by the houses, floating under their skin. The human scale of the two units reinforces identification, while their schematic shape—reminiscent of early childhood drawings—suggests, beyond architectural models, the quintessential idea of home. A series of photographs complements the installation, documenting communist architectural vestiges and the urban devastation that marked the most destructive project of the ‘80s in Bucharest—the development of the Civic Centre.

Offering a critical reconsideration of the recent past and contemporary Romanian reality, Vatamanu and Tudor’s work reflects the uncompromising views of a young and intransigent generation of artists unafraid to look back and question. To examine and process past traumas is indeed essential for the process of re-humanizing an oppressed society and re-building on stable grounds. Bringing focus to still controversial histories, Living Units provides an occasion to explore the political and ethical state of a post-communist society, its disillusions and hopes.

1 Andrei Plesu, “Ideologies between ridiculousness and subversion” in About Happiness in the East and the West, and Other Essays, quote trans. Mona Filip (Bucharest: Humanitas Multimedia, 2006).