Howard Podeswa: A Brief History

Foreword by Mona Filip

Howard Podeswa: A Brief History

Koffler Gallery, 2016

Shard by shard we are released from the tyranny of so-called time.

– Patti Smith 1

Painting takes time – the time it takes to come into being and, later, the time it requires to be seen.

As one of the oldest forms of artistic expression, painting originated from a human desire to capture the experience and dimensionality of the physical realm in an attempt to organize reality and mak sense of the world. However, painting is also a record of time, not only insofar as narrative content – as document of a historical moment or biographical insight – but also as visual evidence of its making. Once completed, the image can be arguably considered immovable and timeless. Yet the viewer’s eye will move across a finished work just as the painter’s has before. Traces of the artist’s process remain evident and compositional decisions release the pictorial space unevenly, offering a journey for the gaze to unfold. The immediacy of past gestures invites a present, durational experience. Time travel happens, as past and present overlap within the seemingly static instance of the painting.

For the past two years, time has been on Howard Podeswa’s mind more than ever. Reflecting on the current state of the world as well as personal trials, he has created a monumental body of work articulating an end-of-times cosmology inspired by artistic and scientific visions. Derived primarily from Dante’s allegories of the afterlife in the Divine Comedy and Stephen Hawking’s quantum theories, the exhibition A Brief History tackles innate existential anxieties, engaging in philosophical speculations about the very notion of time. Signaling a collapse of old global orders, Podeswa’s series moves from a feelin of sorrow and disquiet to one of hope, turning to concepts of astrophysics to explore what may lie beyond our known universe.

Before entering the gallery proper, one encounters an older painting of Podeswa’s, Watching Goya’s Colossus in my Sorels (2009), hanging beside the introductory text panel. Part of his From the Plain of San Isidro series, it depicts a self-portrait of the artist contemplating the somber fields of Francisco Goya’s famous painting. The looming colossus is absent in Podeswa’s version, but shows the crowds fleeing a black chasm that threatens to consume everything – an ominous reminder of dark histories and prophesies of doom, to which the painter bears witness.

A few years later, Podeswa stares into the abyss and summons us to face it with him.

Seamlessly shifting between realism and abstraction within vast canvases, the paintings in A Brief History take time to fully reveal themselves. Their complex and lush surfaces compel the gaze to alternately linger and wander. From darkest depths, their imagery reaches our eye at varying speeds, oscillating between a slow delivery and a sudden hurl forward. Figures and objects hover on the verge of emergence or disappearance. The material sensuality of Podeswa’s brushwork guides the eye across seductive fluctuations in the paint’s texture and thickness over large stretches of subtly modulated colours, drawing us in and demanding our time.

Matter is where the exhibition begins.

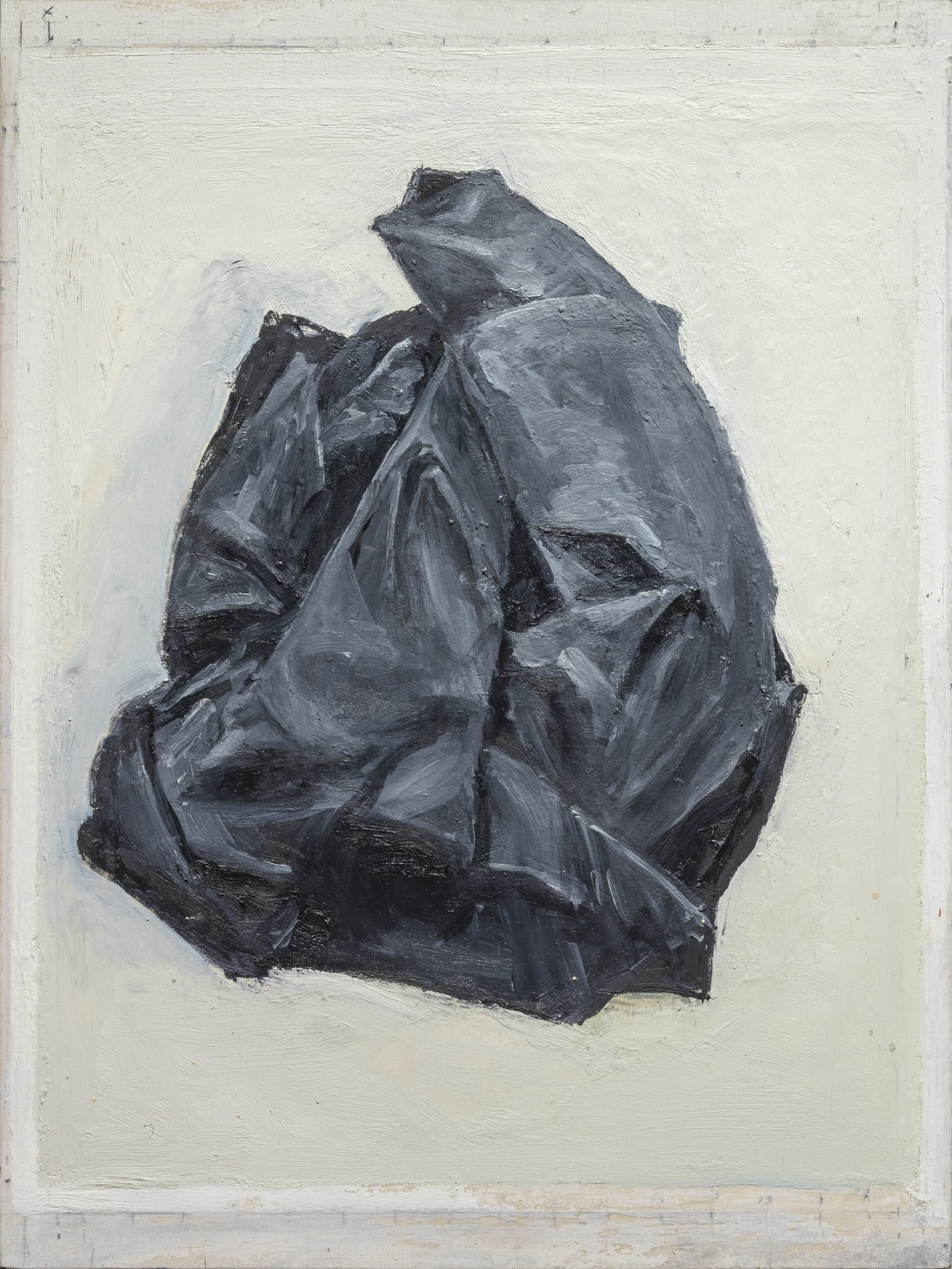

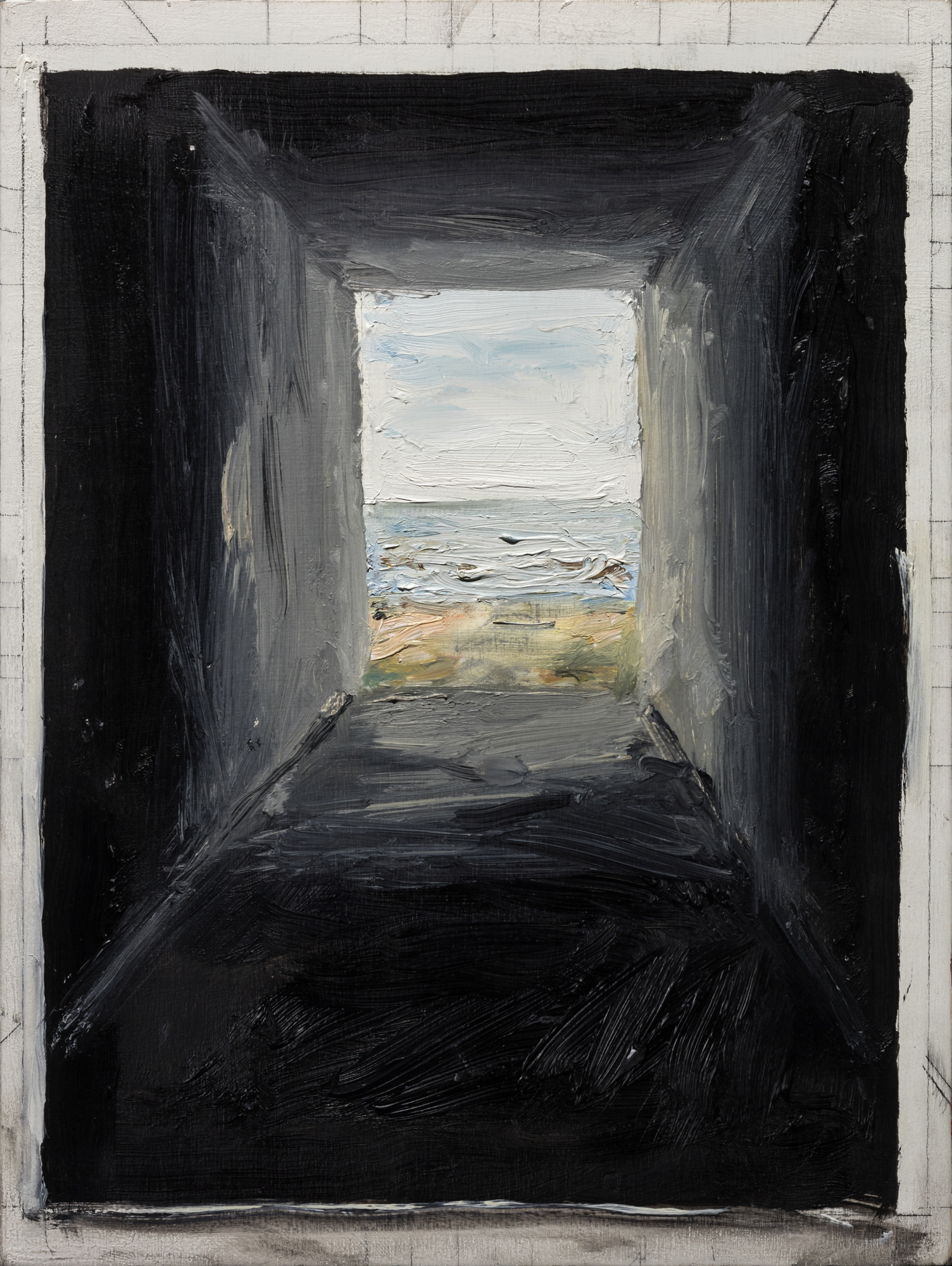

The gallery has been transformed: a black cube occupies most of its centre, separating the architecture into an inner sanctum and a surrounding portico. Two small paintings frame the elongated pronaos. To the left, a little wooden panel, Untitled 2014, offers the image of a crumpled black rag on a creamy white background. To the right, another identically-sized panel, Untitled 2015, opens the perspective from a dark passageway into a luminous opening – a deceptively prosaic beach landscape seen through the rectangular aperture of a culvert.

In the context of a series exploring ideas of hell and heaven, these modest works take on profound significance. The ordinary black cloth reads as a mourning shroud, a veil to be lifted and expose the human condition in its darkest hour. It becomes a monument to lost things, lamenting the loss of the tangible world. The culvert serves as insubstantial counterpart: the path of transcendence from embodied objecthood into limitless and atemporal space.

Between these two small paintings, an open doorway faces the viewer, offering access into the black room. The content of this virtual sanctuary remains hidden from view until the threshold is approached. Three choices lie ahead: follow one of the outer corridors to the left or right, or proceed straight ahead toward the open doorway. The visitor has to decide.

Turning left or right and following the peripheral walkways, a suite of large paintings greets the viewer with a cast of macabre characters and terrifying scenes – as much the direct decedents of Pieter Breugel’s and Francisco Goya’s arsenals of nightmarish ghouls as the horrific stuff of today’s global news. A sinister master of ceremonies wearing a red coat and holding a baton asserts himself as a gatekeeper of hell. He is gone in the next tableau, leaving open the way into a gaping dark pit that swallows the last glimmers of light. Around the corner, another monster with a spider-shaped body floats in a mass of viscous black and ghost-like figures. Further on, a spiral of wretched beings is suspended in free fall and, finally, a skeletal watchdog guards a menacing torture wheel strung up with bodies.

Reminiscent of Dante’s journey through the circles of Inferno, these scenes lead a vertiginous descent into the terrifying bowels of hell, while forming a transitory space toward the innermost chamber and the centrepiece concealed within. Upon entering, one is immediately positioned between two massive paintings and swiftly engulfed in an astonishing force field. To one side is Hell, to the other, Heaven. The poignant, immersive compositions enfold the viewer in an endless universe.

Hell is a black hole. Seemingly all matter, the entire physical world, has been absorbed within its circular confines. Space is contracting, reaching maximum density. Time ends here, with neither sequence of action, nor horizon to provide reference: historical and contemporary events are tossed together in an uninterrupted, perpetual spiral of horrors. There is no escape, as the vicious circle appears to close in.

Then space expands again, slowly panning out into the painting opposite: Heaven. The white expanse surrounding the black ring of hell stretches out, gradually revealing that this is not all there is. A multitude of circles pierce the luminous field, each disclosing glimpses of other visions – fragments of a life encapsulated in memories, perceptual shreds just on the edge of recognition. The limitations and linearity of time and space recede, revealing an essential simultaneity of past, present and future as well as possible parallel worlds that co-exist tantalizingly outside the scope of our awareness.

The mythical ideas of heaven and hell provide Podeswa with an effective artistic stratagem, allowing him to examine humanity’s endeavour to fathom its transient existence while he presents sobering commentary on current global circumstances. His representations combine historical allusions with personal memories, recent natural disasters with social upheavals, in a sweeping view reminding us that painting is an instrument of knowledge, a tool for understanding the world and contemplating the unknown.

Still, A Brief History is also a deeply personal work, stemming from grief and burrowing to the essenc of being as the fundamental question we struggle to decipher. “Life is measured by time but not wholly knowable through it.” 2 Podeswa ultimately imagines us shedding time’s illusory grip, furtively eluding it to grasp the broader view. But an all-encompassing vision is not yet within our reach, as we remain subject to perspective and grounded in our fleeting moment.

We seek to stay present, even as the ghosts attempt to draw us away. 3

1 Patti Smith, M Train (New York/Toronto: Alfred A. Knopf, 2015), 215.

2 Ihor Holubizky, PREDISPOSED (...to thinking through the eye of mutual convenience) (Hamilton: McMaster Museum of Art, 2015), 47.

3 Patti Smith, 247.