Contemporary art unraveling the Dead Sea Scrolls

Exhibition Essay by Mona Filip

Joshua Neustein: Margins

Koffler Gallery, 2009

“So empty are our eyes sometimes,” wrote Reb Waddish, “that the letters of the Book can gradually invade them and, to the rhythm of a music only they know, far From despotic words, dance naked, dance mysterious dances in the sky.” 1

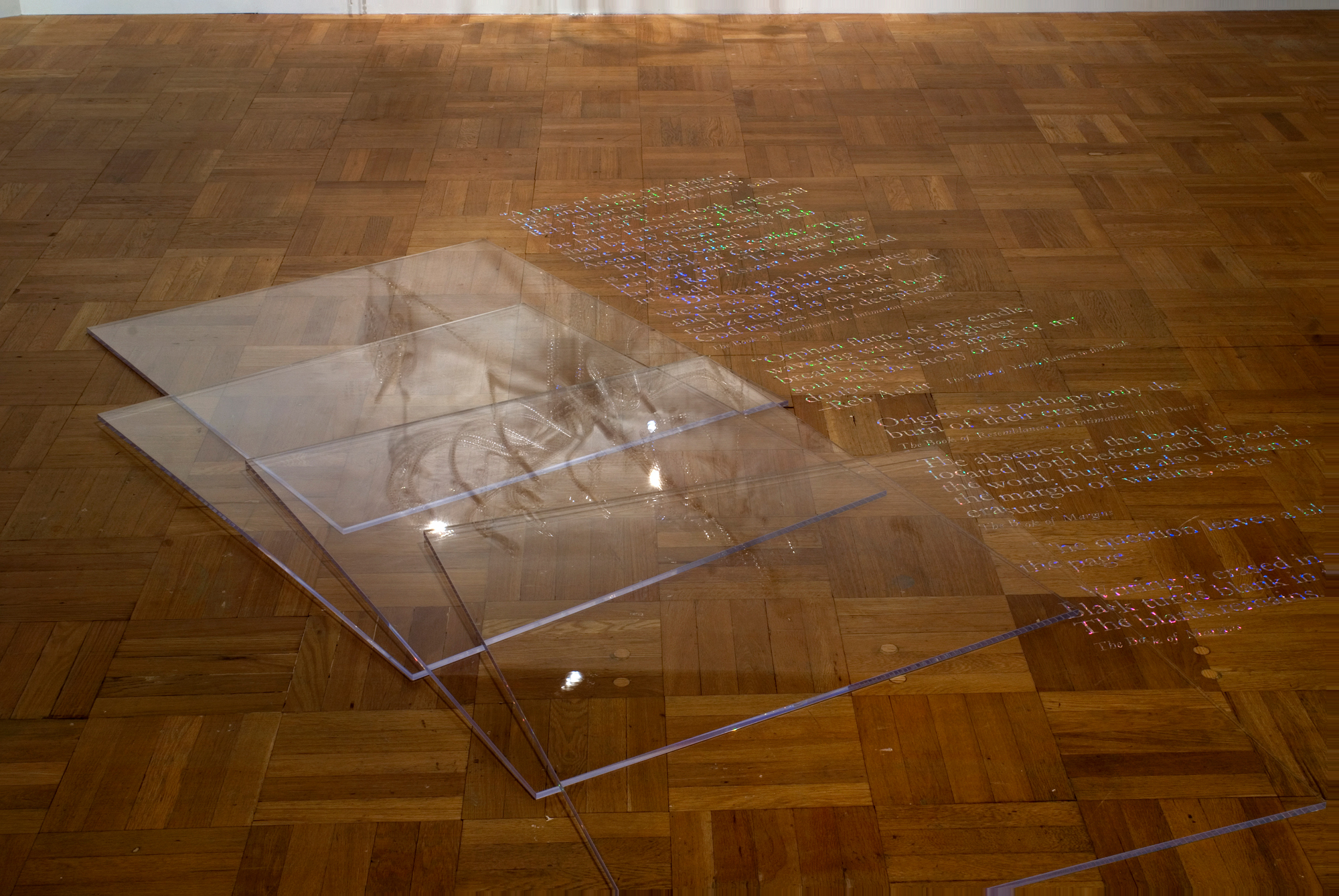

Handwritten with white oil stick on the monumental window overlooking the white angular walls of the Royal Ontario Museumʼs Michael Lee-Chin Crystal, enigmatic words confront the gaze and puzzle the reader. They infiltrate the room, spilling from transparent acrylic sheets onto the walls and floors. A fragile house of cards seems to have crumbled, lured by an enticing beacon: a once glamorous chandelier, emerging from the wall opposite the window. On another wall, large gestural marks have been drawn with graphite and, subsequently, a perfect square has been erased into the dark mass.

Created by New York-based artist Joshua Neustein, Margins is a new installation commissioned in conjunction with the ROMʼs exhibition, Dead Sea Scrolls: Words that Changed the World. Shaping a dialogue with the Scrolls, Neusteinʼs project engages in a poetic, visual reflection on writing, religion and archaeology, approaching these notions with mistrust for dogmas and an intellectual yearning for re-interpreting inherited assumptions.

To speak the language of others, but in the interrogative mode. “Always in a foreign country, the poet uses poetry as an interpreter.” 2

Positioning the Scrolls within a contemporary discussion about cultural traditions, Margins uses Egyptian Jewish poet Edmond Jabès (Cairo, 1912 – Paris, 1991) as a mediator, referencing his critical works concerned with the nature of writing, silence, God, and the Book. Neustein recognizes in Jabèsʼs relationship to writing a parallel to his own artistic process. Living and creating between countries and languages, both artists articulate their work from a position of displacement. Instead of a sense of belonging to a land, they both trace their roots to a deeper connection to the word and to a tradition of reading and questioning the Book. In the installation, Jabèsʼs mysterious meditations and the intimations of the revealed knowledge embodied by the historical texts converge with Neusteinʼs own visual vocabulary to convey the passion and impossibility of writing.

“Are we still writing when we keep harping on the impossibility of writing?”

Are we not, rather, bristling against this impossibility, making sure that writing is always possible even where its very impossibility has been confirmed?” 3

Through drawing, sculptural and textual elements, Neusteinʼs piece re-enacts the emergence of the word piercing the silence with luminous presence. The lavish ruin of the chandelier embedded into the gallery wall radiates as the core of the work—a strange archaeological relic excavated into visibility. Two of its numerous branches surfacing from the plaster are still lit, having survived the wreckage. The chandelier glistens only as a dim reminder of its once glorious presence.

Over the years, Neustein has developed a distinctive visual vocabulary of materials and motifs. Since 1991, when the piece entitled How History Became Geography was presented at the Barbican Arts Centre, the chandelier has played a central role in many of his installations, including Light on the Ashes (1996), Aschenbach (1997), and Domestic Tranquility (2000). Suggestive of great halls of learning and cultural sophistication, this elegant object becomes emblematic of enlightenment, alluding to a striving for discovery and interpretation. It usually offers an indispensable counterpart to the obliterating darkness of Neusteinʼs other essential materials: soot and ash. However, in the process of illuminating, the sumptuous lighting fixture draws more attention to itself rather than anything else around it, revealing a self-centred nature. In Margins, under a faded guise, the chandelier takes on a dual sense of warning and hope.

Unraveling from the window sill towards the chandelierʼs brightness, transparent acrylic sheets lay collapsed on the floor, bearing shimmering texts printed in light-refracting vinyl. Drawn out by light, handwriting turns into typography, setting words into crystallized form. The texts shy away from the viewer, fading and re-appearing, shifting as light moves across their surface, making them difficult to read just as it claims to reveal them. The script escapes the page, crossing margins into the space where writing struggles to uncover what is not yet written.

“Silence is inside the word as something to be read. A book is forever to be lost.”

“Your book?”

“Perhaps the book erased so many times that only a mere inkling of it is left.”

“The book of our silence, the desert.”

“Yes, they are like sand, those soft, crumbly bits of eraser around our deleted words and in the end, O treacherous light or, rather, wound, the stubborn, mad hope of a possible bond, this perverse worm, this maggot in the sun.” 5

Another element in the installation is the drawing on the side wall—a silent witness offering another key to the reading. Within an accumulation of thick graphite marks, Neustein erased a square. The residual erasure bits generated in the process are collected into a glassine envelope and pinned above the drawing on the wall. Preserved with ironic museological concern, nothing is wasted, nor forgotten. The artistʼs successive gestures of drawing and erasing on the bare wall vainly attempt to recover the blank slate. Instead, the marks are rendered even more indelible, the act of erasure revealing their resilient memory. The original potential of the empty surface remains elusive.

In the study of the Talmud—one of the central texts of Judaic tradition recording rabbinic discussions on law, ethics, customs, and history—the margins of the bookʼs pages become an essential territory. While the centre holds the text fragment to be examined, the wide borders are the space of exploration and interpretation, continually expanding with each layer of commentary. Erasing the centre or rendering it transparent, Neustein underscores the marginsʼ prolific grounds, contesting the authority of inherited discourses while acknowledging an enduring, albeit fragile, bond. The centre opens both to recollection and replacement.

Erasing His Name, God multiplied the roads. 6

With characteristically post-modern scepticism and a penchant for questioning rather than finding answers, both Neustein and Jabès approach the ideas of God and religion as culturally inherited notions that need to be addressed. The scorched desert of contemporary intellectual wondering, just like Qumran7, is a fertile expanse of nothingness that can yield the unknown, the invisible. Archaeology unearths dormant traces of history, while writing pushes at the edge of silence to bring forth the unsaid. Similarly, Margins explores apparent and concealed ideas of the Dead Sea Scrolls, exposing them to the light of our times.

1 Edmond Jabès, The Book of Resemblances, II. Intimations The Desert, (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 1990) p. 31. All quotes included in this essay appear in Margins.

2 Ibid, p. 39.

3 Edmond Jabès, The Book of Resemblances, III. The Ineffaceable The Unperceived, (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 1990) p. 31.

4 For a more extensive analysis of the chandelierʼs symbolism see Arthur C. Dantoʼs essay on Joshua Neustein in Unnatural Wonders: Essays from the Gap Between Art and Life (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005), pp. 308-309.

5 Edmond Jabès, The Book of Resemblances, II. Intimations The Desert, (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 1990) p. 7.

6 Edmond Jabès, The Book of Margins, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993), p. 94.

7 Site in the Judean Desert by the Dead Sea, close to the caves where the Scrolls were discovered.