Caroline Monnet: Pizandawatc / The One Who Listens / Celui qui écoute

Exhibition Essay by Mona Filip

Pizandawatc / The One Who Listens / Celui qui écoute

Art Museum at the University of Toronto, 2024

Too often, the act of looking leads to imposing oneself on the seen. Listening enables a different kind of comprehension than plain sight allows.

Knowing the sounds and resonances of a place, its whispers and stories, means understanding it more intimately than by contemplating its landscapes. And being receptive to what the land has to tell opens one up to being shaped by it, rather than moulding it to one’s own desires.

The Anishinaabemowin title of Caroline Monnet’s exhibition, Pizandawatc, comes from the traditional name of the artist’s maternal family before surnames were changed in Kitigan Zibi by the Oblates. Meaning "the one who listens," the title honours the artist’s great-great-grandmother, Mani Pizandawatc, who was the first in her family to have her territory divided into reserves. At the same time, it references a way of being in the world, in relation, in continuity, reflected throughout Monnet’s artistic practice. Of Anishinaabe and French descent, Monnet draws upon her bi-cultural experience to grapple with colonialism’s impact, subverting its oppressive systems with Indigenous worldviews and methodologies. Her distinctive, powerful aesthetic combines elements of popular and traditional visual cultures with tropes of modernist abstraction to create a new visual vocabulary, potent and poignant.

Exploring the notion of territory from the perspective of cultural attachment and ancestral memory, Pizandawatc articulates new visions that harken both to Indigenous legacies and futures. Monnet’s first solo exhibition at a public gallery in Toronto, the project comprises a survey of the artist’s prolific production, centering on a new series of sculptures that reveal the connection between language and land, offering poetic strategies of reclamation and intergenerational transmission. Linked to temporality, orality, and knowledge sharing, sound plays an important part in Monnet’s artistic practice. Integrating the Anishinaabe language, she devises a critical framework that explores the influence of oral history and cross-generational heritage.

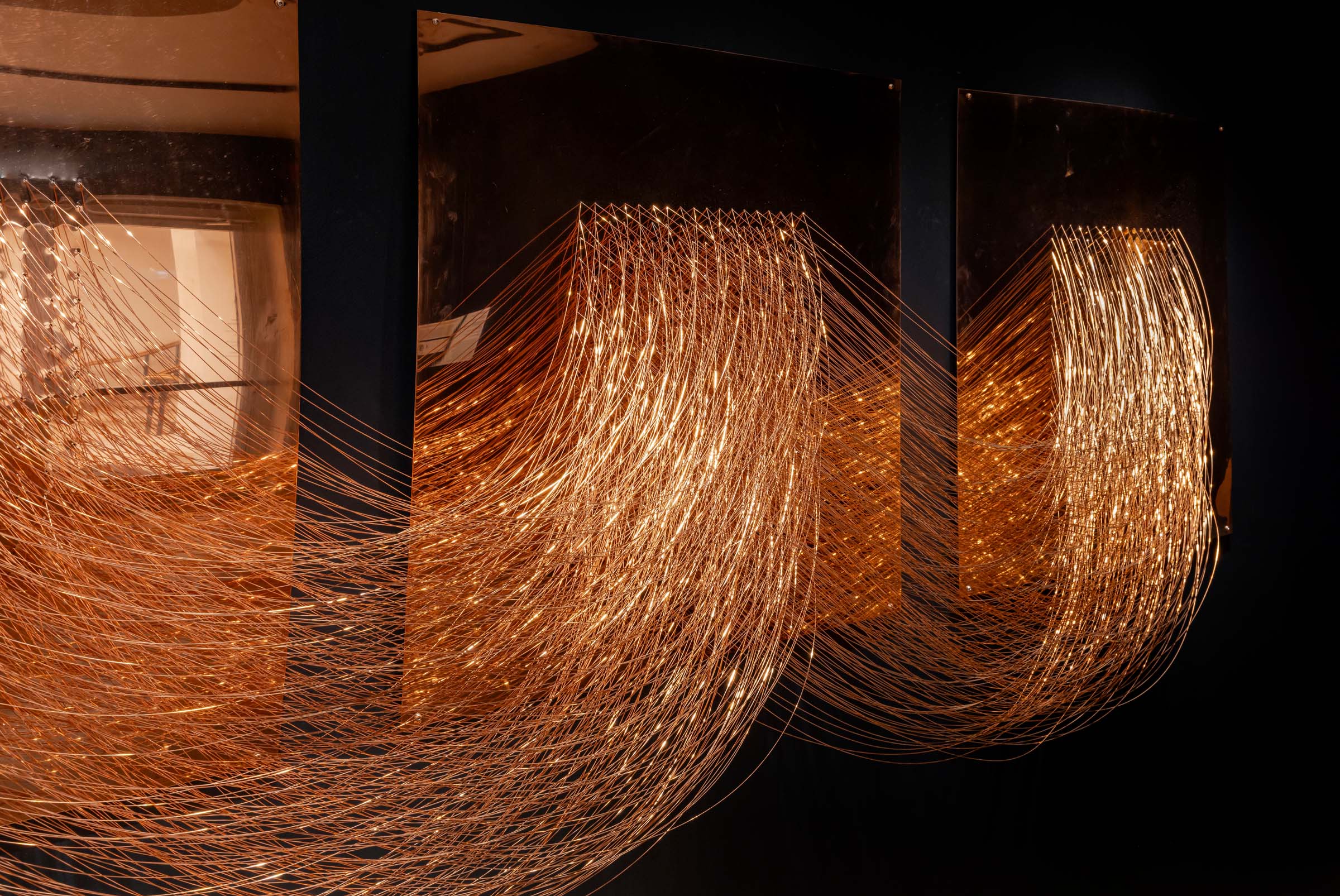

Monnet’s new body of work in Pizandawatc continues her considerations of sound and sculpture first conceptualized in The Flow Between Hard Places, presented at the 2019 Toronto Biennale. Conceived partly in wood, a natural material deeply significant to the Anishinaabe territory, and partly in bronze, the new series records the sound of Anishinaabemowin and features of the land into sculpture. Driven by an impulse to materialize speech into durable physical form in order to preserve it, Monnet attempts to counter the ephemeral nature of the uttered word and to reclaim the Anishinaabe language by recording its resonance in layered native and industrial wood. Evoking the relationship of idiom to the land inhabited and how the Anishinaabeg traditionally named it, these works examine the influence of topography on the rhythms of languages and cultures, envisioning the territory as a living form of knowledge transfer over generations.

Each of the four large sculptures punctuating the entrance to the exhibition depicts a different phrase encapsulating the power of nature and the passage of time. Derived from a process of memory and a desire to make the material speak, the undulating wooden shapes manifest the sound waves created by saying words like Nindanweb apii dagwaaging—When It’s Fall, I Rest—in Anishinaabemowin. Wood is central to this series, as an important material for the Anishinaabeg. Monnet’s grandfather was a lumberjack in his young years, and her ancestors saw their traditional territory ravaged by massive clear-cutting to supply the industries of the Canadian capital. Bronze is also of particular interest to Monnet as it contains copper —the primary metal in earliest alloys used by the Anishinaabeg before the arrival of Europeans. Investigating the impact of human activity on the territory and in its understanding over generations, Monnet retrieves pieces of wood naturally modified by weather, water, or beavers to create bronze moulds, which she places in direct dialogue with the sound sculptures.

Expanding around this significant new series, the exhibition integrates a range of recent and older works that explore related ideas, offering a comprehensive view of Monnet’s complex aesthetic vocabulary, polyvalent material dexterity, and cohesive conceptual investigation. A selection of mixed media, video, and installation works connect themes and materials across the artist’s practice, contextualizing specific directions and shaping meaningful considerations on cultural heritage and its relationship to the land. Over time, Monnet’s work has consistently examined colonial structures of control over land, the detrimental impact of the construction industry on the environment, its consequences on Indigenous displacement and dwelling on reserves, and the devastation of ancestral territories in the deceitful pursuit of progress.

Skilfully amalgamating incongruent visual forms and material connotations, Monnet develops thoughtful processes to alter construction supplies and invest them with new meaning. Insulation, water barrier membrane, oriented strand board, plywood, copper, wool glass, and concrete generate transformative devices to reflect on the centrality of the land and its resources in Anishinaabe spirituality and history, and to affirm its resilience in confronting colonial exploitation. The techniques of weaving, embroidering, and imprinting assert forms of connection and transmission, of communication across time, space, and psychological divides. Geometric motifs inspired by Anishinaabe patterns passed down through generations of matriarchs override corporate logos, investing contractor-grade materials with sacred symbolism. The divided territory is reassembled and sutured through traditional designs and methodologies carrying longsuppressed Indigenous knowledge.

Whether minimal or monumental, Monnet’s works channel deep connections with both ancestral and contemporary cultural resources. They reveal the embodied ways in which memory persists and reverberates within the territory, addressing community across generations and underscoring interconnectedness within the natural world as far as the eye can listen.