Sameer Farooq: A Heap of Random Sweepings

Exhibition Essay by Mona Filip

Sameer Farooq: A Heap of Random Sweepings

Koffler Gallery, 2021

[. . .] an ordered world is not the world order.

– Martin Buber1

[. . .] not artifacts, never artifacts and not objects either. These are things with agency, these are our cultural belongings.

– Candice Hopkins2

These histories are not histories but presences.

– Dan Hicks3

Artworks work upon us, if we open ourselves to the encounter. On initial approach, the space of the Koffler Gallery, where artist Sameer Farooq has assembled sculptures, prints, poetry and sound into an immersive installation, evokes the familiar site of a museum. However, one quickly discovers that what is seen is not as it first seems. Within the dark walls that house Farooq’s exhibition A Heap of Random Sweepings, large structures and objects choreographed throughout the space create a graceful tableau conveying the illusion of museological display; yet each work skilfully undermines the essential premise of vitrines, pedestals and didactics as holding devices for colonial spoils. Emulating appearances while disrupting intentions, Farooq entices us into a deeply poetic space to reflect on the fraught and violent histories of anthropological and encyclopaedic museums – their colonial origins, structures and impulses.

| Every object and image in this ensemble seems caught in the process of disappearing or becoming, confronting viewers as apparitions emerging to meet their gaze. Nothing is on the walls; everything has been moved into the space on rolling tables and dollies, settled carefully into an expectant grid. Framed photographs hang in irregular configurations on lofty easels. Tall glass panels secured by concrete blocks hold up shimmering prints on dark paper. Benches – clean-cut blocks painted the same dark tone as the walls and artwork supports – punctuate the formation, creating distinct vantage points throughout. Solemn, droning music with deep guitar tones and echoing reverb that sinks heavily into one’s ribcage provides an ominous soundtrack to the scene. The installation’s physical arrangement is meant to change several times throughout the exhibition’s run, emphasizing the fluidity of thought necessary for shifting entrenched practices. It is a mobile stage set for an unseen drama. |

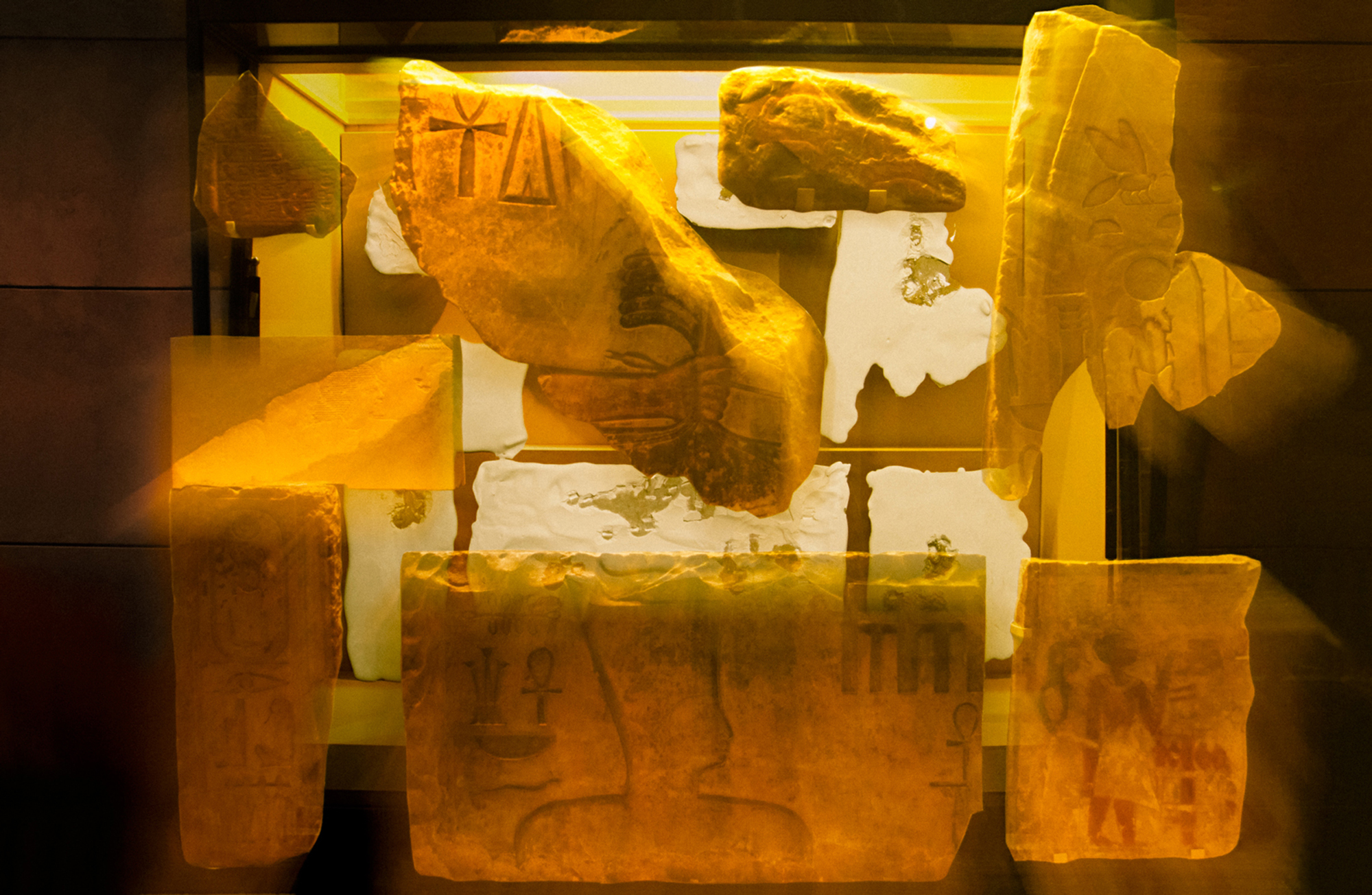

In Farooq’s Restitution Series (2020–2021), three sculptures and eight photographs evoke the format and arrangements of museum cabinets that hoard cultural belongings extracted and assimilated into encyclopaedic collections from various ;

| parts of the world – ritual masks, devotional sculptures, royal symbols, weapons, pottery, animal bones, tusks and minerals. The works are based on documentation amassed by the artist over years of travel to different international institutions. However, this series does not merely reproduce museological devices. Farooq uses the specific properties of casting and photographic processes to destabilize the stasis of such displays and undo their claim of infinite hold. The objects are no longer captive, no longer frozen in time. |

British archaeology professor and curator Dan Hicks notes: “Through the medium of loot, museums became a device to make the remembrance of colonial violence and cultural destruction [. . .] endure – and to do the work of creating difference between the Global North and the Global South, ‘civilization’ and ‘barbarism’ – which in the hands of the anthropology curator became a temporal rather than simply a geographical difference.”4 As custodians of colonial spoils,museums weaponized time, manipulating geographic distance into historical anachronism, fixing distant cultures into an archaic past in order to consolidate ideological arguments of difference and deficit that would validate domination.

Considering the impact of the forceful detention of artifacts sustained over decades as well as the implications of their repatriation, Farooq articulates a possible new aesthetic. “These histories that are layered onto these belongings when they come into the museum are often fragmented, filled with gaps and silences,” writes Indigenous curator Candice Hopkins.5 Instead of glass cases storing rows of ceramic vessels, spear heads and variously sized Buddha statuettes, blocks of white plaster stand on metal tables, punctured by cavernous holes and swells bearing the imprints of former displays. Using casts to generate physical traces through the shaping and removal of objects, Farooq translates the gesture of displacement into solid form. Making and unmaking, he moulds the negative space, the breathing air around the objects, and reveals the marks left behind by the departed. Their ghostly residue stuck in crevices wrought by their removal present us with hollow recesses and protruding reverberations for our gaze to caress and fill. Weighed by gravity yet suspended in grace, the sculptures’ monolithic presence asks us to spend time with the absences they conjure. Photography developed alongside the anthropological museum as a colonial device of capture and extraction, from a similar aspiration to collect, order and control. They were both established, as Hicks describes, as “documentary interventions in the fabric of time itself, to create a timeless past in the present as a weapon that generates alterity.”6 The frame of the camera, like the frame of the museum case, was meant to freeze and hold captive, enshrining violence aspatrimony.

Farooq’s photographs in the Restitution Series rely on analogue processes of collaging and layering transparencies filters and lighting while using an improvised dolly to create actual physical movement and portray objects in a state of transition out of the frame. Lifted from their mounts, the liberated artifacts leave dark holes hovering in their place, like spots of discoloured paint marking the wall space where a picture once hung. Bright hues of red, blue, green, hot pink and yellow ochre tint the images into vivid monochromes, awakening the vitrines from years of suspended animation to a moment of action when perhaps these objects’ journeys can finally reach resolution.

“Through a camera, through a museum display, through a gun that shoots twice, an event, through violence, can encompass a kind of fragmentation that means it can’t quite end.”7 The aggression perpetrated by the colonizers extends through time in a continuous present through the stagnant display of the museum, re-enacted daily as long as cultural belongings remain entombed, their agency denied. To change the purpose and modes of operations of museums begins with an admission that their contents are not the salvage of a dead past but, in Hicks’ terms, “unfinished events” in need of rightful closure.8 As long as encyclopaedic museums vainly continue to regard themselves as expert caretakers ofuniversal heritage, a truthful understanding of world cultures is impossible.

Colonial ways of classifying yield a skewed world order of blatantly unjust imbalance. Farooq’s exhibition takes its title from a text fragment of Ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus – “The fairest order in the world is a heap of random sweepings.” 9 Contained in this apparent paradox is the idea that the most organized and just attempt at a universal order is equally as flawed or filled with balance and beauty as an arbitrary pile of refuse. Considering these opposing notions, Farooq’s composed but changeable assembly invites us to interrogate our relationship with museums and the ordering narratives they uphold.

While raising questions about provenance and repatriation, the sculptures and images convened in this installation articulate new visions for repurposing the emptied spaces of museums devoid of their plunder. Going back to art’s origins in invocation and ritual to recall the possibilities offered by sustained engagement, Farooq invites us to envision what museums might become through the mechanics of restitution, what they may shift to collect and document, and what kind of experiences they could nurture. The installation he creates elicits prolonged attention, asking us to look intently and enter into dialogue with these objects’ presences as well as the absences they evoke.

Strategically placed benches encourage moments of extended contemplation. The audio environment composed by Farooq’s collaborator Gabie Strong sets a deliberate and slow pace. Structured as a cycle of four movements that begin quietly and reach a discomforting crescendo, the musical piece is designed to guide the visitor to spend six minutes ateach vantage point, immersed in active looking. A bell sound marks the intervals. However, this contemplative mood does not induce serene detachment. The artworks offer themselves as portals that may reveal an intrinsic potential transcending their aesthetic value.

And yet, in the sunlight, the silver triangle glittered. It reflected light. Fire, Mr. Tagomi thought. Not dank or dark object at all. Not heavy, weary, but pulsing with life. The high realm, aspect of yang: empyrean, ethereal. As befits work of art. [. . .]

Body of yin, soul of yang. Metal and fire unified. The outer and inner; microcosmos in my palm. [. . .]

And my attention is fixed; I can’t look away. Spellbound by mesmerizing shimmering surface which I can no longer control. No longer free to dismiss.

Now talk to me, he told it. [. . .]

Where am I? Out of my world, my space and time.

The silver triangle disoriented me. I broke from my moorings and hence stand on nothing.10

Artworks work upon us. The work of art is to push our imagination toward the possibility of new ideas, new thoughts, new worlds. They show us the work to be done and call on us to do it. A Heap of Random Sweepings urges us to conceive of new museums restored on ethical intentions and a genuine desire to relate. Farooq’s works assembled in the exhibition are born from dialogue and further nurture the possibility of relation. What his vision proposes resonates with the words of art historian Griselda Pollock: “The museum is remade daily as the realized promise of art as work.”11

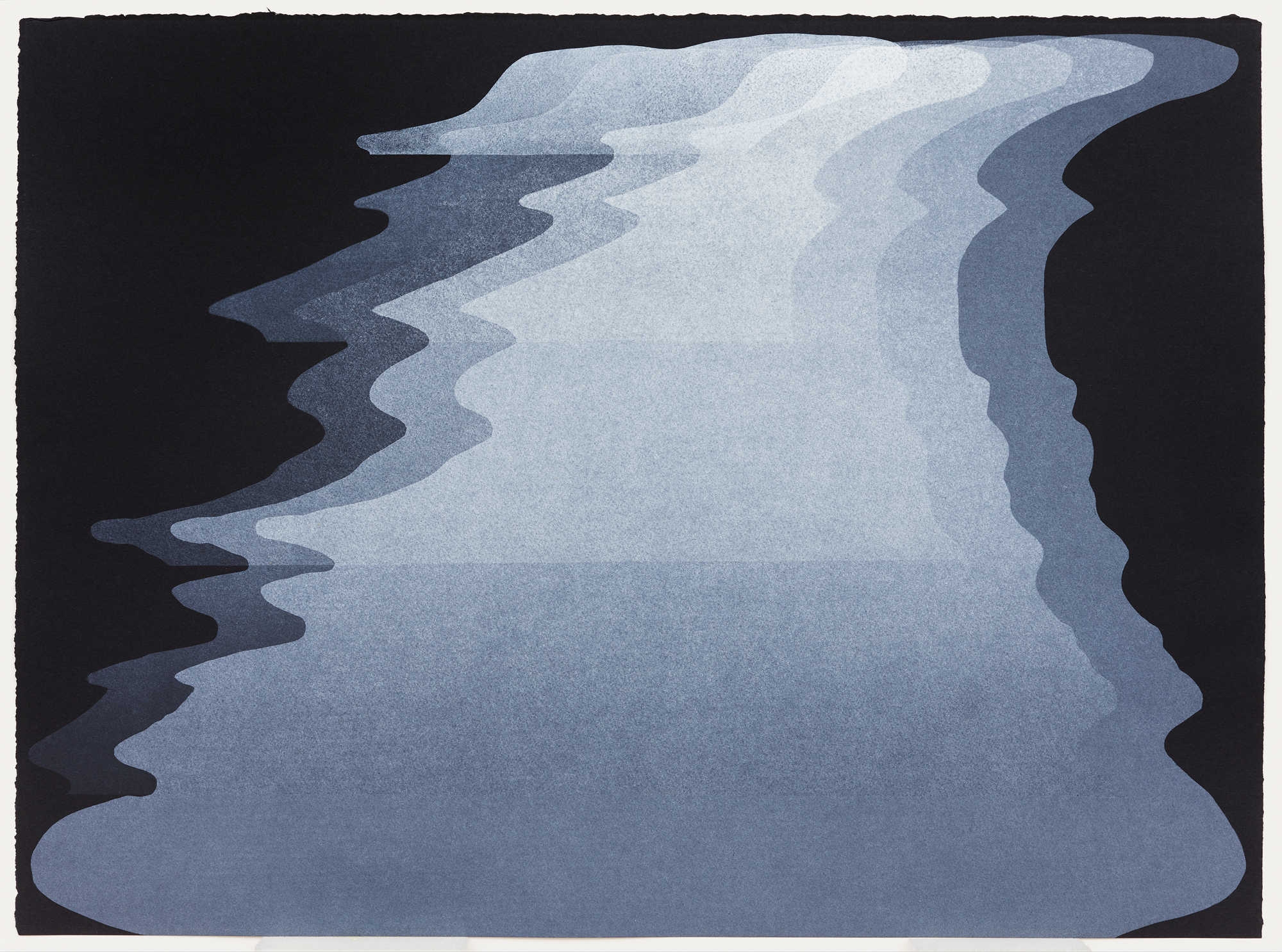

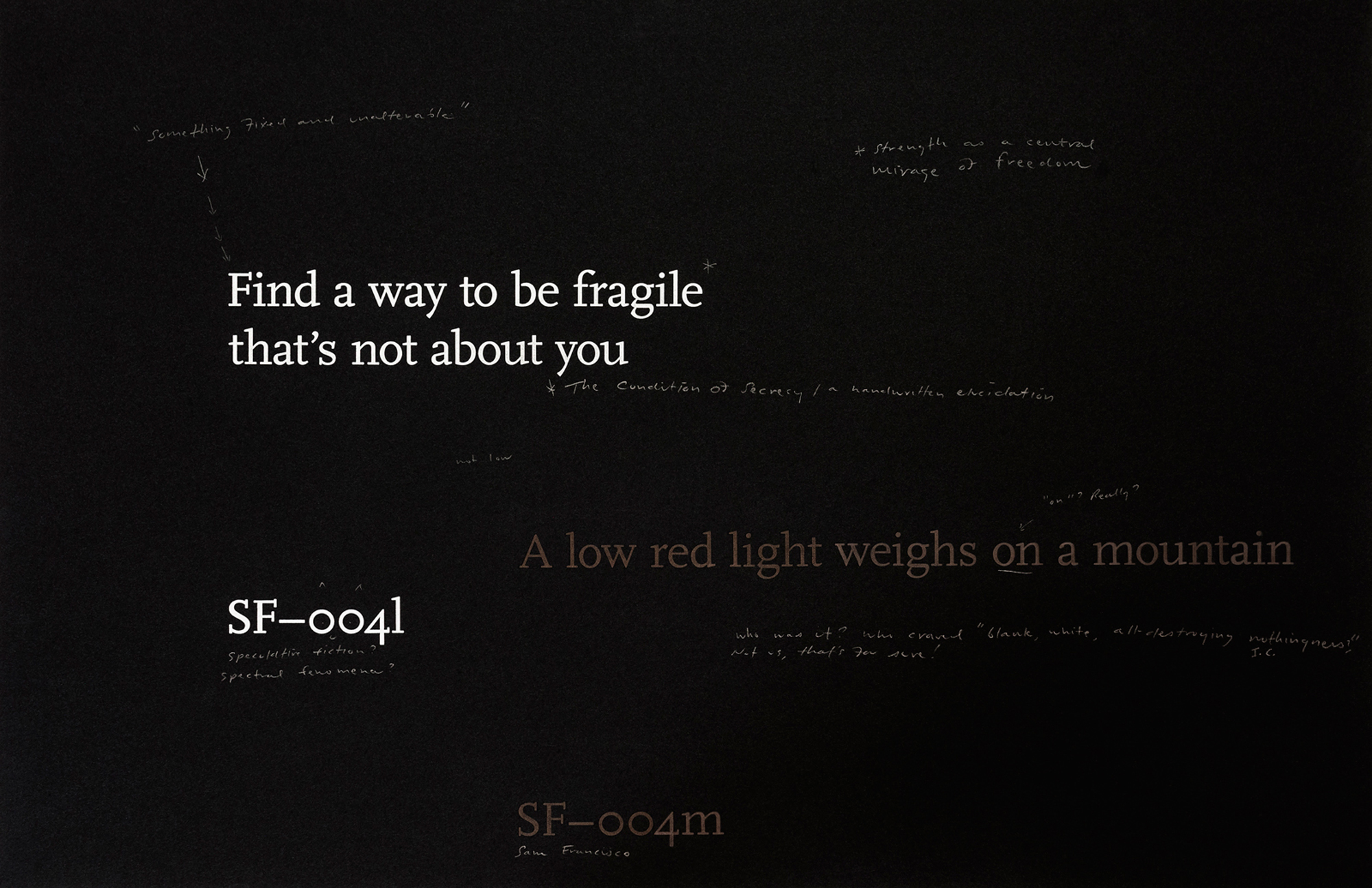

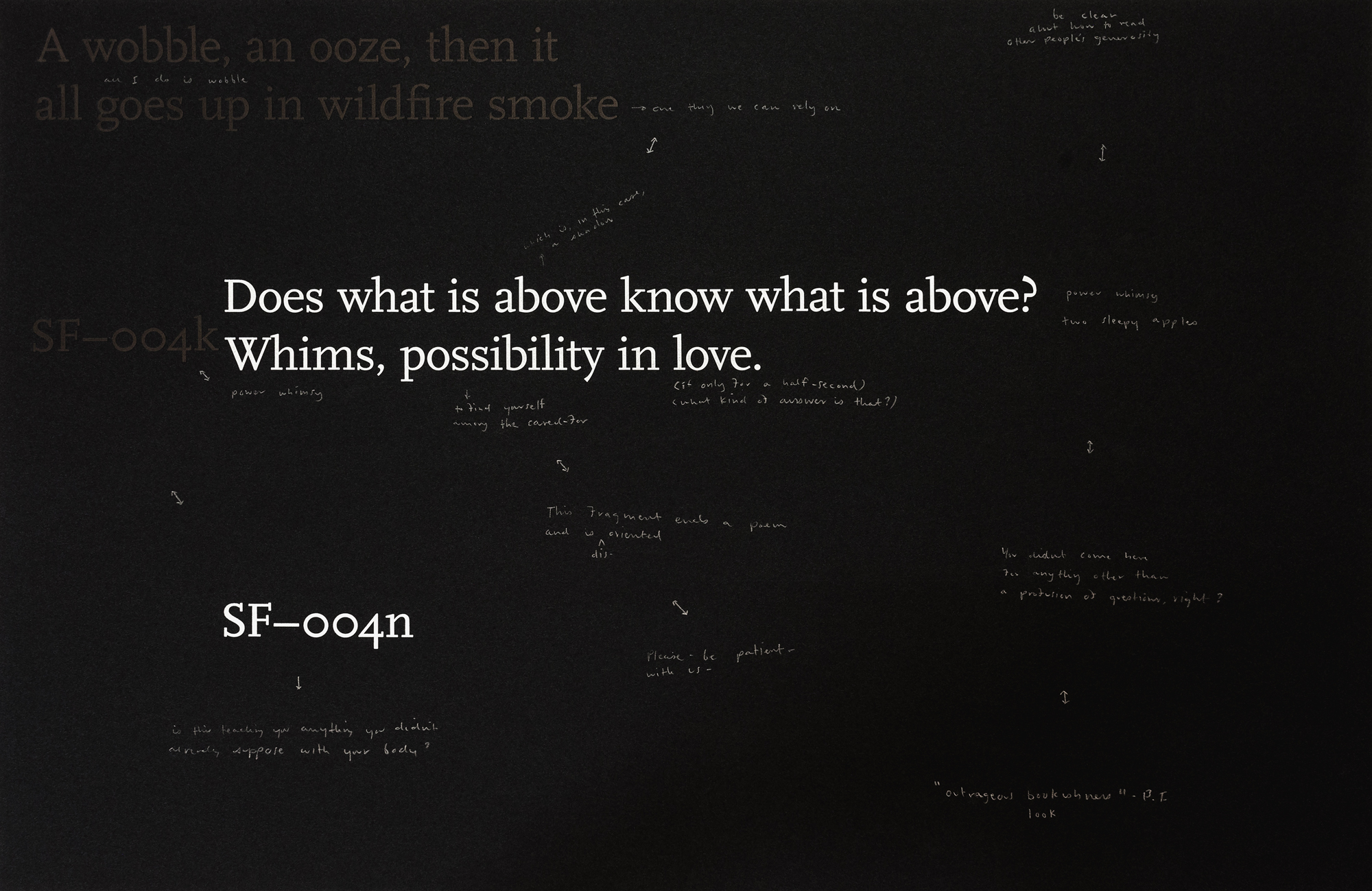

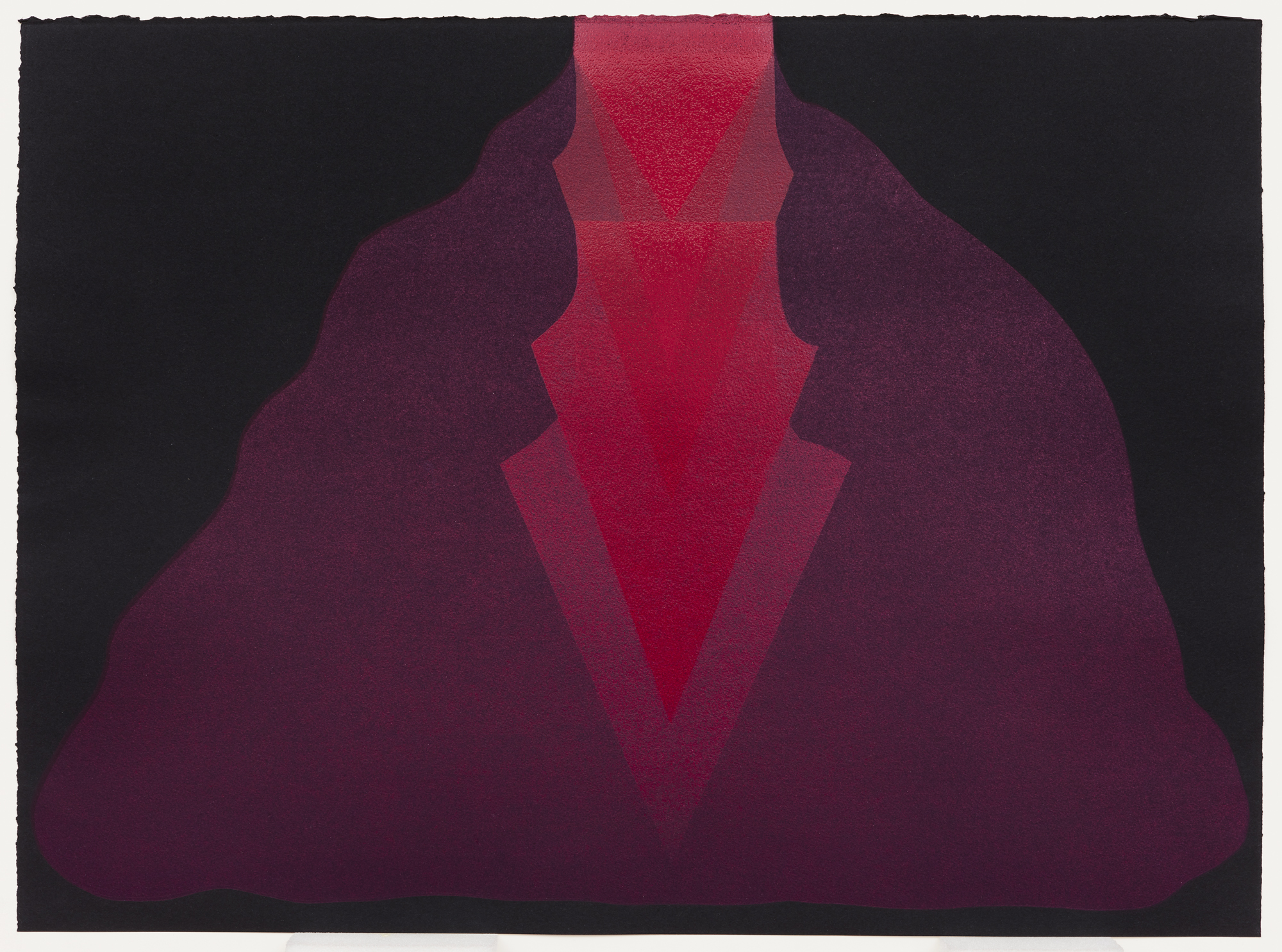

In creating the group of monoprints entitled 24 Affections (2019), Farooq collaborated with poet Jared Stanley, sending him each image to respond to with lyrical captions. This dialogic correspondence produced a luminous series of layered shapes accompanied on their versos by labels that unsettle the rigid format of institutional didactics and imagine deeper conversations about connection and vulnerability. They stand interspersed throughout the room, held up by glass and concrete mounts based on the iconic design of Brazilian modernist architect Lina Bo Bardi.

Derived from Farooq’s rigorous engagement with both physical and mindful practices of meditation, these monochrome abstractions excavate internal images sourced from his body and consciousness. As with every work presented in this installation, an illusion of movement occurs through the formal treatment of otherwise still images. From the darkness of the black paper, each form materializes gradually, defined by transparent layers of colour applied successively to saturate a vibrant core. Paired as diptychs, the progress of one figure continues in its counterpart. These bursts of colourful light stand suspended in mid-air, pressed between monumental panes of glass. On the other side of the panels, Stanley’s poetic riffs take time to reveal themselves as well. A layer of white text claims precedence, but closer inspection uncovers a palimpsest of handwritten annotations and embossed texts on the edge of visibility.

A similar process of meditation and visualization yielded the centrepiece of the installation – If it were possible to collect all navels of the world on the steps to ASCENSION (2019). Staged on a white tiered pedestal modelled after an Egyptian Museum display, a set of 112 small, organic-looking objects made of fired clay are organized in a harmonious repertoire of earthy hues ranging from deep black-browns and blues through burnt siennas to sandy greys. Some are glazed and glossy, others rough and textured; some are decorated with embossed markings. Each is differently sized and proportioned. Nevertheless, the same fundamental shape echoes through every variation: rounded, conical, pointing upward.

| Issued from the artist’s intuitive hands and psyche without preliminary research, this form proved to have a rich history of symbolism and ritual function. Known in many cultures as the navel of the world – from the Greek omphalos – this rounded, pointed stone marked the spiritual and foundational centre of a community. Usually placed at the core of a religious site or sanctuary, it was believed to facilitate connection with the sacred. The ascending shape is archetypal, representing the axis mundi – a cosmic pillar embodied in different forms and located at the centre of the universe. It was imagined to link the underworld of the dead, the earthly plane of human existence, and the divine heavens, allowing for communication and passage between the sacred and the profane. |

| Farooq’s ASCENSION emulates the organizing museum methodologies that tend to relegate objects to basic traits and exhibit them in matching groupings, aesthetically ordered regardless of their nature and intended purpose. While clearly the navel of the world was always imagined to be unique, here we encounter several dozen manifestations of the same |

They decorated with ribbons Poured water and caressed us We were prayed over so much We never knew there were others There are so many others What if our spiritual whimsy Actually did rush through The intimate veil of your surprise Pierced as you stand there Actually did rush through Like that

| With the disappointment of revealed ubiquity comes a different kind of epiphany: the world has no centre. Because the centre is a multitude and omnipresent, there is no hierarchy. There is instead a sense of commonality – an acknowledgement of kinship. And the museum might as well collect a heap of random sweepings. |

| What then may these sweepings be? The answers may vary greatly based on subjective desires for the public and distinctive mandates for the institutions. But what Farooq proposes to consider is the kind of experience a museum space may be conducive to providing instead of a sheer catalogue of contents. |

Anthropological and encyclopaedic museums were established to articulate and enforce a Eurocentric, white supremacist worldview that relies on othering. Plundered cultural belongings were objectified and manipulated so they could serve the purpose of the colonizer. Held within museum vaults and cabinets, they became imprinted with museological mind- sets and systems, their nature altered and subdued. Deprived of their community life, extracted from their intended networks of relations, things that were never mere artifacts were isolated and reified. In philosophical terms, “What has become an It is then taken as an It, experienced and used as an It, employed along with other things for the project of finding one’s way in the world, and eventually for the project of ‘conquering’ the world.”12 When things are used and experienced instead of being engaged in dialogic form, the power to relate is lost.

Artworks have the capacity to work upon us, to facilitate a form of self-realization that can only happen in relation. They can be partners of dialogue, affecting us to our core. As philosopher Martin Buber writes, “That which confronts me is fulfilled through the encounter through which it enters into the world of things in order to remain incessantly effective, incessantly It – but also infinitely able to become again a You, enchanting and inspiring. It becomes ‘incarnate’: out of the flood of spaceless and timeless presence it rises to the shore of continued existence.”13 Art can make us more genuinely ourselves and authentically open to each other if we allow it to work upon us. Museums can provide the space that makes this transformation possible, embracing art’s models of engagement through deep thoughtfulness and meaning making, enabling it to destabilize our assumptions and shift our perspectives.

I require a You to become; becoming I, I say You.

All actual life is encounter.14

1 Martin Buber, I and Thou (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1970), 82.

2 Candice Hopkins, “Repatriation Otherwise: How Protocols of Belonging are Shifting the Museological Frame” (essay published as part of the digital forum Constellations. Indigenous Contemporary Art from the Americas, Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo, Mexico City, Mexico, October 2020).

3 Dan Hicks, The Brutish Museums: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution (London: Pluto Press, 2020), 212.

4 Hicks, 182.5 Hopkins, “Repatriation Otherwise.”

6 Hicks, 182.

7 Hicks, 12.

8 Dan Hicks, “Ten Thousand Unfinished Events,” in The Brutish Museums, 230–234.

9 Charles H. Kahn, The Art and Thought of Heraclitus: An edition of the fragments with translation and commentary (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 85.

10 Philip K. Dick, The Man in the High Castle (Boston: Mariner Books, 2011), 243–246.

11 Griselda Pollock, Museums After Modernism: Strategies of Engagement (Malden: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2007), 30.

12 Buber, 91.

13 Buber, 65–66.

14 Buber, 62.